Dairy is frequently billed as a vital bone-builder; so does allowing children to go vegan put them at risk of osteoporosis in later life? Researcher Network member, Imogen Allen discusses her research project and sets out to answer this question.

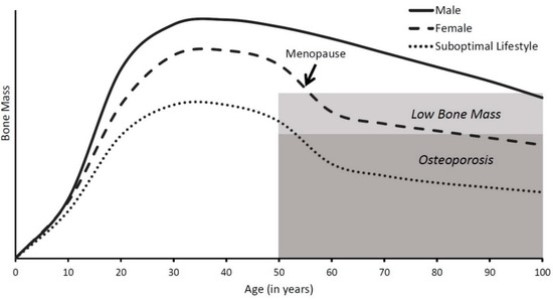

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem affecting 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men worldwide (Sözen et al., 2017). It is characterised by “low bone mass, micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to enhanced bone fragility and consequent increase in fracture risk” (Tuck and Francis, 2002). Bone mass is rapidly accrued during childhood and peaks by the age of 30 (Hodges et al., 2019a). As such, the condition has been referred to as “a paediatric disease with geriatric consequences” (Hightowler, 2000). Exercise and exposure to sunlight both have a role to play in staving off osteoporosis (Lanou, 2009). Diet, particularly dairy consumption, is also frequently cited as an important factor. Dairy is often marketed as being critical to bone health because it is naturally rich in bone-building nutrients, especially calcium (Sahni et al., 2015).

Figure 1: Peak Bone Mass Curve (Hodges et al., 2019a).

Figure 1: Peak Bone Mass Curve (Hodges et al., 2019a).

In recent years, the number of individuals excluding dairy from their diet is on the rise. The number of vegans have quadrupled between 2014-2018 and 10% of children aged 8-16 are now vegan or vegetarian (Society, 2019). If dairy’s bone-building reputation is well-founded, one might expect vegan children to be exposed to risk of osteoporosis as they age. To determine whether such concerns are valid, it is necessary firstly to examine the relationship between dairy consumption and bone health amongst this age group; secondly to analyse studies comparing the bone status and diets of vegans to non-vegans; and thirdly, to assess whether bone-building plant-based alternatives exist.

DAIRY CONSUMPTION AND BONE HEALTH IN CHILDREN

The relationship between dairy consumption during childhood/adolescence and bone health is contentious. A cross sectional study using data from NHANES III showed the risk of osteoporotic fractures in non Hispanic white women over the age of 50 was twice as high in those who drank less milk between the ages 5-12 compared to those with a higher intake (Fardellone, 2019). Additionally, individuals drinking less milk had lower hip bone mineral content and bone mineral density in adulthood. These results are supported by other observational studies using retrospective questionnaires of milk consumption (Fardellone, 2019). Although these results are limited due to potential recall bias of historical milk intake, they emphasize the importance of dairy during childhood in maintaining bone health.

A meta analysis of randomized controlled trials by (Huncharek et al., 2008), provides the most high quality scientific evidence to date. It shows a bone-benefitting effect of dairy in children with low baseline intakes. However, this may say more about calcium than about dairy, as the analysis suggested calcium supplements may have similar effects. Future studies should focus on whether dairy contains components besides calcium that have an additional benefit to bone health. More controlled studies comparing dairy calcium versus supplementation would also be helpful.

BONE HEALTH IN VEGAN CHILDREN

Few studies have investigated the relationship between the bone mineral content of children/adolescents and vegan diets. Out of the studies available, one small family case study (2 adults and 2 children) showed that all members had decreased bone density at important parts of the skeleton as well as low vitamin D and calcium levels (Ambroszkiewicz et al., 2010). Additionally, an early case control study highlighted vegan adolescents as having a lower bone mineral content compared to controls (Parsons et al., 1997). Although both of these studies attributed low intake of calcium and vitamin D to these results, (Parsons et al., 1997) put forward additional explanations: unlike (Ambroszkiewicz et al., 2010), they also found inadequate energy and protein intake in the subjects, which is known to negatively impact bone health. Additionally, they suggested that the high fibre content of vegan diets is likely to impede bone metabolism by interfering with calcium absorption and increasing the excretion of sex hormones.

CHOOSING APPROPRIATE PLANT-BASED ALTERNATIVES

If the studies discussed above are correct, then vegan diets that are low in calcium, vitamin D, energy or protein and/or high in fibre could lead to poor bone health in children or adolescents. In the UK, the particular importance of dairy as a source of some of these nutrients for children is emphasized by the NHS (2018), which advises parents not to cut out dairy without consulting a GP or dietician first. This suggests that exclusion of this dietary component without a suitable substitute could present dangers to vegan children/adolescents. However, it should be possible to consume a vegan diet and meet nutritional requirements providing a degree of dietary vigilance is maintained.

Individuals excluding dairy will need to substitute its high calcium and protein content. Thanks to a recent boom in innovation, plant-based milk and dairy substitutes have entered the UK market in abundance (Wired, 2018). Many of these are fortified with calcium. Although questions have been raised about the bioavailability of calcium in certain products, fortified soy based milk substitutes have been shown to contain similar levels of equally bioavailable calcium as cow’s milk (Makinen et al., 2015). This suggests soy-based substitutes should be an adequate replacement. Additionally, there are many plant-based calcium rich sources, particularly beans and greens (Lanou, 2009), although it is again worth noting concerns about bioavailability due to the quantities of fibre, phytates and oxalates present in such foods (Hodges et al., 2019b). Nevertheless, a combination of soy-based milk substitutes and high intake of calcium-rich plant-based foods should be sufficient to meet calcium requirements in children and adolescents.

Moving on to protein, none of the literature reviewed has investigated the effects of low protein intake and bone health specifically in this age group. With regards to adults, a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies found mainly positive trends associated with high protein diets and bone health (Shams-White et al., 2017). Even so, there are plant-based dairy substitutes available which rival their traditional counterparts in protein content; AlproTM’s soy milk alternative contains only 0.5g less protein than semi-skimmed cow’s milk per 100ml. Although many plant-based protein sources are regarded to be incomplete, a varied intake of different plant proteins should be acceptable in meeting individual’s requirements (Fields and Ruddy, 2016).

Vegans who use supplements and/or substitute dairy for fortified plant-based milk alternatives may find these have bone-health benefits over cow’s milk. Most plant-based substitutes are fortified with vitamin D, whereas cow’s milk naturally contains very little and is more rarely fortified. Vitamin D increases intestinal absorption of calcium (Christakos et al., 2011). Ultimately, regardless of diet-type, supplement consumption has been shown to be the best predictor of vitamin D levels (Chan et al., 2009).

CONCLUSION

In light of the findings above, cautious non-vegan parents may not be in a hurry to ditch dairy from their children’s diet. However, this does not necessarily mean that parents are necessarily putting vegan children at risk of osteoporosis. Well planned vegan diets should be able to replace the nutrients previously provided by dairy in adequate, bioavailable quantities whilst also potentially reducing the risk of other chronic health problems such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer and cardio vascular disease (The Vegan Society, 2019; Tonstad et al. 2013; Key et al., 2014; Le & Sabaté 2014) . Nevertheless, considering the concerns raised by the studies discussed, more comparative analyses are required, particularly considering that the numbers of vegans are projected to increase rapidly over the coming years. Ideally, future long term studies will follow vegan and omnivorous children throughout their lives, comparing their risk of osteoporosis in old age. For now, shorter term case-control studies could compare bone health indicators of vegan children to their non-vegan peers, paying particular attention to their relative calcium intake and status.

Comment from The Vegan Society's in-house Dietitian, Heather Russell:

“People often associate dairy with calcium and bone health. A well-planned vegan diet can provide all the nutrients required for growth and development but the evidence base is limited at present, so it’s important that the implications of switching to a vegan diet are considered by researchers. Imogen highlights that many factors affect our bones and particularly draws attention to the role of fortified plant milk, which is recognised as a rich source of calcium by the UK’s Eatwell Guide. She also points out that soya-based products are a valuable source of high quality protein for growing vegans. Here at The Vegan Society, we’re passionate about helping people to follow a healthy vegan lifestyle. We provide an array of resources, including nutrition guides for every stage of life and bone health tips.

Bibliography

Ambroszkiewicz, J, Klemarczyk, W, Gajewska, J. & Chełchowska, M. (2010). The influence of vegan diet on bone mineral density and biochemical bone turnover markers. Paediatric Endocrinology, 16, 201-204.

Chan, J, Jaceldo-Siegl, K & Fraser, G. (2009). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of vegetarians, partial vegetarians, and nonvegetarians: the Adventist Health Study-2. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89, 1686-92.

Christakos, S, Dhawan, P, Porta, A. & Mady, L. (2011). Vitamin D and Intestinal Calcium Absorption. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 347, 25-29.

Fardellone, P. (2019). The effect of milk consumption on bone and fracture incidence, an update. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, 759-764.

Fields, H & Ruddy, B. (2016). How to Monitor and Advise Vegans to Ensure Adequate Nutrient Intake The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 116, 96-99.

Hightowler, L. (2000). Osteoporosis: pediatric disease with geriatric consequences. Orthopaedic nursing, 19, 59-62.

Hodges, J, Cao, S, Cladis, D & Weaver, C. (2019a). Lactose Intolerance and Bone Health: The Challenge of Ensuring Adequate Calcium Intake. Nutrients, 11, 718.

Hodges, JK, Cao, S, Cladis, DP & Weaver, CM. (2019b). Lactose Intolerance and Bone Health: The Challenge of Ensuring Adequate Calcium Intake. Nutrients, 11, 718.

Huncharek, M, Muscat, J & Kupelnick, B. (2008). Impact of dairy products and dietary calcium on bone-mineral content in children: results of a meta-analysis. Bone, 43, 312–21.

Key TJ, Appleby PN, Crowe FL et al. (2014) Cancer in British vegetarians: updated analyses of 4998 incident cancers in a cohort of 32,491 meat eaters, 8612 fish eaters, 18,298 vegetarians, and 2246 vegans 1, 2, 3, 4. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100: 378–85. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24898235 (accessed 26 June 2019).

Lanou, AJ. (2009). Should dairy be recommended as part of a healthy vegetarian diet? Counterpoint. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89, 1638S–1642S.

Le LT & Sabaté J. (2014) Beyond Meatless, the Health Effects of Vegan Diets: Findings from the Adventist Cohorts. Nutrients 6: 2131-47. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24871675 (accessed 26 June 2019).

Makinen, OE, Wanhalinna, V, Zannini, E & Arendt, EK. (2015). Foods for Special Dietary Needs: Non-dairy Plant-based Milk Substitutes and Fermented Dairy-type Products. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 56, 340.

Parsons, T, van Dusseldorp, M, van der Vliet, M & van de Werken, K. (1997). Reduced Bone Mass in Dutch Adolescents Fed a Macrobiotic Diet in Early Life. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 12, 1486-94.

Sahni, S., Mangano, K. M., McLean, R. R., Hannan, M. T. & Kiel, D. P. (2015). Dietary Approaches for Bone Health: Lessons from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Current Osteoporosis Reports, 13, 245–255.

Shams-White, M, Chung, M, Mengxi, D & Zhuxuan, F. (2017). Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105, 1528–43.

Sözen, T, Özışık, L & Başaran, NÇ. (2017). An overview and management of osteoporosis. European Journal of Rheumatology, 4, 46–56.

The Vegan Society (2019). Statistics. Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/news/media/statistics (accessed 04 July 2019).

Tonstad S, Steward K, Oda K et al. (2013). Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 23: 292-9. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21983060 (accessed 26 June 2019).

Tuck, SP & Francis, RM. (2002). Osteoporosis. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 78.

The views expressed by our Research News contributors are not necessarily the views of The Vegan Society.

The views expressed by our Research News contributors are not necessarily the views of The Vegan Society.