RAC member Dr Shireen Kassam rates her top science papers supporting plant-based nutrition of 2023

The Times Health Commission reported on the rising level of chronic ill health in the UK. Not only is this negatively impacting quality of life, but it is rapidly becoming unaffordable for a health service and an economy that are both near or at breaking point. A third of middle-aged adults have at least two chronic health conditions. On average we are spending the last decade of our lives in ill health, and for people with lower incomes this can be as long as 20 years. The Commission rightly recognises the huge contribution that unhealthy diets and lifestyles are making to this national health crisis. The symptoms of this crisis are the rising rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes in both children and adults, but the report clearly states that “diet, a lack of physical activity, smoking and alcohol account for around 80 per cent of non-communicable diseases.”

The Insight report from The Health Foundation further emphasises the deteriorating health of the UK population. The number of people living with major illness is projected to increase by 2.5 million by 2040, more than a third. This translates to a change from almost 1 in 6 adults in 2019 (6.7 million) living with major illness to almost 1 in 5 by 2040 (9.1 million). Although this rise is mainly in people over the age of 70, even those aged 20–69 years are seeing significant rises in rates of chronic illness.

The UK is not unique, with all countries seeing rising rates of chronic conditions (non-communicable diseases). This is and will be further exacerbated by climate breakdown, which the World Health Organisation (WHO) describes as the greatest threat to human health. This year the international community has been highlighting the health consequences of climate change. The 2023 Lancet Countdown report on climate change and health finds that 12.2 million premature deaths globally are a result of unhealthy diets, whilst at the same time the production of food remains hugely unsustainable.

Health Inequality: sadly, access to healthy nutrition is not available to those who need it the most and therefore unhealthy diets contribute to the growing issue of health disparities and inequity. This year’s report from the Food Foundation provides stark statistics relating to our broken food system:

- The poorest fifth of UK households would need to spend 50% of their disposable income on food to meet the cost of the government-recommended healthy diet. This compares to just 11% for the richest fifth.

- Healthy life expectancy in the most deprived tenth of the population is 19 years less for women and 18 years less for men than in the least deprived tenth.

- More healthy foods are over twice as expensive per calorie as less healthy foods.

- By 2050, emissions from the food system will be four times higher than the level that is needed if the UK is to meet its net zero target.

Shan, Z. et al. (2023) ‘Healthy eating patterns and risk of total and cause-specific mortality’, JAMA Internal Medicine, 183(2), pp. 142–153. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6117 [published correction appears in (2023) JAMA Internal Medicine, 183(6), p. 627]

What do all healthy diet patterns share in common?

The start of the year saw the publication of this key paper, which provided guidance on what defines a healthy diet pattern. The study analysed health data collected over 36 years from 75,230 women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study and 44,085 men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. All participants were free of cardiovascular disease or cancer at the beginning of the study and completed dietary questionnaires every four years. Dietary data were scored based on each of the four dietary pattern indexes (Healthy Eating Index 2015, Alternate Mediterranean Diet, Healthful Plant-based Diet Index and Alternate Healthy Eating Index). All share key components including high consumption of whole grains, fruit, vegetables, nuts and legumes. They differ on the emphasis placed on the inclusion of fish, dairy and lean meats.

Scoring highly on any of the four dietary indices was associated with a lower risk of premature death from all causes and from cardiovascular disease, cancer and respiratory disease. Higher scores on the Alternate Mediterranean Diet and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index were also associated with lower risk of death from neurodegenerative disease. The results were consistent for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic people. Overall, the magnitude of effect of one of these healthy diet patterns was a reduction in early death of around 20%.

The authors conclude that their results support “long-term health benefits by adherence to various healthy eating patterns that can be adopted based on individuals’ health needs, food preferences, and cultural traditions, although all these diet patterns encourage high consumption of healthy plant-based foods.”

Fadnes, L.T. et al. (2023) ‘Life expectancy can increase by up to 10 years following sustained shifts towards healthier diets in the United Kingdom’, Nature Food, 4, pp. 961–965. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00868-w

Adding years to life

Despite knowing a lot about the key components of a healthy diet pattern and having evidence-based dietary guidance, the vast majority of people are not adhering to these guidelines. In the UK, less than 0.1% of the population meet the recommendation of our dietary guideline – The Eatwell Guide. This paper used a previously developed model for estimating the gain or loss in life expectancy in men and women aged 40–70 years following sustained dietary changes. The researchers used dietary data from 467,354 participants of the UK Biobank study. The median dietary patterns in the UK were categorised as the intake level within the mid-quintile intake of each of the food groups.

The results showed that the longevity-associated dietary pattern had moderate intakes of whole grains, fruit, fish and white meat; a high intake of milk and dairy, vegetables, nuts and legumes; a relatively low intake of eggs, red meat and sugar-sweetened beverages; and a low intake of refined grains and processed meat. Some of the impact of these foods was attenuated when adjusting for body mass index. The unhealthy dietary pattern contained no or limited amounts of whole grains, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, fish, milk and dairy and white meat, but substantial intakes of processed meat, eggs, refined grains and sugar-sweetened beverages. The strongest positive associations with mortality were for sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meat, while the strongest inverse associations with mortality were for whole grains, fruit and nuts.

The results showed that regardless of age, a shift towards a healthier diet pattern resulted in an increase in life expectancy. Shifting from the median UK diet to a healthy diet increased life expectancy by around 3 years for a 40-year-old and 1.7 years for a 70-year-old. Shifting from an unhealthy diet to a healthy diet increased life expectancy by 10 years in a 40-year-old and 5 years in a 70-year-old. The estimates were slightly lower after adjusting for energy intake and body mass index. Consuming less sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats and eating more whole grains, fruits and nuts were estimated to result in the biggest improvements in life expectancy.

Prior studies have shown similar gains in life expectancy and importantly healthy life expectancy when shifting to a healthy diet pattern with benefits demonstrated regardless of age. For example, a similar analysis based on a US population showed significant gains in life expectancy when shifting from a typical Western diet to a healthy diet pattern regardless of age and with the greatest gains from consuming more whole grains, legumes and nuts.

The researchers of this study call for policy changes that support people to access healthier foods, including health-orientated food taxes and subsidises, improving the food environment and public sector catering and the need for multi-sector action including from the food industry.

Thompson, A.S. et al. (2023) ‘Association of healthful plant-based diet adherence with risk of mortality and major chronic diseases among adults in the UK’, JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e234714. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.4714

Plant-based diets can improve health outcomes

It’s great to see the plant-based diet index (PDI) being used to analyse data from a UK cohort. The analysis included 126,394 participants from the UK Biobank study recruited between 2006 and 2010 and followed until 2021, providing 10–12 years of follow-up. The mean age was 56 years, and the majority of participants were White. Data were collected on diet, lifestyle and health, and dietary intake was scored using the plant-based diet index – the overall PDI, unhealthy PDI (uPDI) and healthy PDI (hPDI). Of note, healthy plant foods are fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts and seeds. Participants with higher hPDI scores compared to lower scores had a 16% reduction in risk of death from all causes, whereas participants with higher uPDI scores had a 23% increased risk of death. Higher hPDI scores were associated with a 7% reduction in cancer risk, 8% reduction in cardiovascular disease, 16% reduction in ischaemic stroke and 14% reduction in heart attacks. In addition, there was a benefit of greater adherence to the hPDI for those at higher genetic risk of cardiovascular disease. In contrast, higher uPDI scores were also associated with a higher risk of cancer (10%) and a higher risk of dying from cancer (19%) and up to a 23% increased risk of cardiovascular disease. There was no association of the hPDI or uPDI with fracture risk or haemorrhagic stroke, which is relevant given results from vegan cohorts that suggest there may be an increased risk. You can read more about bone health and stroke in my previous articles.

The authors of this study conclude: “Overall, our results suggest that a healthful plant-based dietary pattern – characterized by lower amounts of animal foods, sugary drinks, snacks and desserts, refined grains, potatoes, and fruit juices – is associated with lower risks of mortality and major chronic diseases."

Gardner, C.D. et al. (2023) ‘Dietary patterns: alignment with American Heart Association 2021 dietary guidance: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association’, Circulation, 147(22), pp. 1715–1730. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001146

Which popular diets are heart healthy?

Dietary guidelines for promotion of cardiovascular health recommend the consumption of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, whilst limiting or avoiding red and processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods. Plant sources of protein and fat should be prioritised. In most guidelines, fish consumption continues to be promoted. The 2021 American Heart Association guidelines do not consider meat essential, but write: “if meat or poultry is desired, choose lean cuts and unprocessed forms”.

This new statement from the American Heart Association examines 10 popular dietary patterns in the US and considers how well they align with their 2021 guidance on heart healthy diets. The diets considered are DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension-style), Mediterranean-style, pescatarian, ovo/lacto-vegetarian, vegan, low-fat, very low-fat, low-carbohydrate, Paleolithic (Paleo) and very low-carbohydrate/ketogenic patterns. They are ranked Tier 1–4 based on how well they meet heart healthy dietary guidelines.

The analysis shows that Tier 1 and 2 dietary patterns are all plant predominant. Tier 1 includes Mediterranean, vegetarian and pescatarian. Tier 2 includes vegan and low-fat diets. Vegan diets rank lower than vegetarian because the authors consider them restrictive and difficult to sustain over the longer term. In addition, concerns are raised around protein and vitamin B12 sufficiency.

All the low-carb, meat-heavy diets are ranged in Tier 3 and 4, showing lower alignment with optimal nutrient intakes.

I find this statement a positive endorsement of meat-free diets. The avoidance of fish does not seem to present the authors with any specific concerns but instead they state: “The budgetary savings and environmental benefits of ovo/lacto-vegetarian diets relative to animal flesh-containing diets may be a desirable feature for some patients.” There is also emphasis on respecting cultural practices and food preferences. Those of us who have followed a vegan diet for several years can reassure others that it is neither restrictive nor unsustainable, but joyful and delicious. With a small amount of knowledge and skill, any concerns about nutrient deficiencies can easily be overcome through appropriate planning and selective supplementation. This is a thumbs up for veggie and vegan diets for cardiovascular health.

Landry, M.J. et al. (2023) ‘Cardiometabolic effects of omnivorous vs vegan diets in identical twins: a randomized clinical trial’, JAMA Network Open, 6(11), e2344457. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44457

Healthy vegan vs omnirous for heart health

I often get asked whether a plant-based diet is really healthier than an optimised omnivorous diet. Now we have the answer, or at least part of the answer.

This study in 22 pairs of identical twins randomised participants to a healthy vegan or healthy omnivorous diet (one twin per diet) and was followed for eight weeks. The primary outcome was change in LDL-cholesterol level. Secondary outcome measures were changes in cardiometabolic factors (plasma lipids, glucose, and insulin levels and serum trimethylamine N-oxide level), plasma vitamin B12 level and body weight. After eight weeks, compared with twins randomised to an omnivorous diet, those on a vegan diet experienced significant decreases in LDL-cholesterol and fasting insulin levels and reductions in body weight. The omnivorous group also lost weight but to a lesser degree. Vegans also experienced a larger but non-significant absolute median decrease in fasting HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, vitamin B12, glucose and TMAO levels compared with omnivores.

Important points to note. The participants were generally healthy individuals. Food was provided to participants for the first four weeks, but they could also purchase and consume snacks to meet their energy requirements following guidance from health educators. This was not a weight loss study, so no energy restriction was prescribed with participants asked to eat until they were satiated. As a consequence, the vegan participants consumed around 200kcal less than the omnivorous group and thus lost more weight, which could have been the reason for the positive finding. The omnivorous group improved their diet quality as a result of consuming more vegetables and whole grains and less added sugar and refined grains and also lost weight. Vegans reported a lower degree of diet satisfaction than the omnivorous group, especially when eating out in the second half of the study. Given the short-term nature of the study, we don’t know if diet satisfaction would have changed as new habits are formed and sustained. The fact that the participants are identical twins helps to control for genetic and shared experiences, making the findings more likely to be due to diet alone.

Overall, this study finds that in healthy individuals an optimised vegan diet has health advantages when compared to an optimised omnivorous diet. Although the study is small and of short duration, it provides actionable evidence for those wanting to improve their health. The lower diet satisfaction may be a barrier for some, but public health initiatives could provide support to normalise this way of eating and help individuals to improve their cooking skills. Vitamin B12 supplementation is essential on a vegan diet. This study is good news for people, the planet and the animals.

The study is the subject of a new Netflix docuseries launching 1 January 2024, You Are What You Eat.

Koch, C.A., Kjeldsen, E.W. and Frikke-Schmidt, R. (2023) ‘Vegetarian or vegan diets and blood lipids: a meta-analysis of randomized trials’, European Heart Journal, 44(28), pp. 2609–2622. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad211

Plant-based diets and blood lipids

A key benefit of vegan and vegetarian diets is the positive impact on blood lipid level and thus cardiovascular health. This large meta-analysis of 30 randomised studies following adults for over 18 years showed that vegetarian and vegan diets consistently lead to lower levels of blood total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and apolipoprotein B (apoB). These blood lipids are directly implicated in the development of atherosclerosis – fatty plaques in the arteries – that over the long-term cause heart attacks and strokes. In case you are not familiar with apoB, this is a protein found in the LDL-particles that is key to their ability to cause atherosclerosis. ApoB is found in all atherosclerosis-causing lipoproteins, so it is actually a better marker of cardiovascular risk than LDL-cholesterol. However, the standard assessment for cardiovascular risk, certainly in the UK, still relies on LDL-cholesterol levels. The aim is to keep LDL-cholesterol as low as possible over the whole lifespan, as lifetime exposure to elevated levels creates the increase in risk rather than the level at just one point in time. Reducing LDL-cholesterol levels has a HUGE impact on cardiovascular risk. Each 1mmol/L (38.7 mg/dL) reduction in LDL-cholesterol is associated with an average 22% reduction in major vascular event risk and a 10% reduction in all-cause mortality over a five-year period.

The researchers found that both vegetarian and vegan diets reduced total and LDL-cholesterol to a similar degree. This is the first meta-analysis to assess impact on apoB levels, but vegetarian and vegan diets were not analysed separately for this outcome.

Interestingly, vegan and vegetarian diets did not result in lowering of triglyceride (TG) levels. This is not a surprise and several studies have shown that a Mediterranean-style diet may actually be more effective at lowering TG levels, mainly because of the higher content of unsaturated fatty acids. Main messages are to emphasise unsaturated sources of fat, from olive oils, nuts, seeds and avocados. Avoid refined carbohydrates, replacing them with whole grains, maintain a healthy weight, avoid alcohol and, for some people, reducing intake of carbohydrate-rich foods and replacing them with plant foods higher in protein and fats may help.

Overall, meat-free diets are a great choice for optimising cardiovascular risk factors, especially blood lipids. A reminder of the recent practice statement from the American Society for Preventative Cardiology that recommends a variety of plant-predominant diets for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, including Mediterranean, DASH, healthy vegetarian and exclusively plant-based diets.

You can listen to me present this paper at the MyNutriWeb Journal Club.

Gibbs, J. and Leung, G.-K. (2023) ‘The effect of plant-based and mycoprotein-based meat substitute consumption on cardiometabolic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled intervention trials’, Dietetics, 2(1), pp. 104–122. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics2010009

Impact of plant-based meat alternatives (PBMAs)

A common refrain from omnivores is that plant-based diets are at risk of being high in ultra-processed foods given the proliferation of PBMAs. Even though PBMAs are not required in the diet, they provide an additional option for people transitioning away from consuming meat. It’s therefore good to see more studies addressing their health impacts when compared to meat consumption.

The aim of this meta-analysis was to assess the short-term effects of meat substitutes on important cardiometabolic biomarkers (total cholesterol, TC; LDL-cholesterol, LDL-C; HDL-cholesterol, HDL-C; triglycerides, TG; systolic blood pressure, SBP; diastolic blood pressure, DBP; fasting blood glucose, FBG; and weight) in controlled clinical trials. The analysis included 12 studies and separated PBMAs from mycoprotein products. The results showed that the consumption of meat substitutes is associated with significant reductions in TC, LDL-C, and TG when compared with the consumption of omnivorous diets. In addition, PBMAs did not have an impact on HDL-C, in contrast to some studies on plant-based diets which show a reduction. PBMAs did not appear to impact the other markers of cardiometabolic health that were assessed – SBP, DBP, FBG and weight – but the level of certainty of these results was low.

There are many reasons why PBMAs, including mycoprotein, may have benefits on cardiometabolic health when compared to meat. In contrast to meat, PBMAs have fibre, are absent in cholesterol, may have lower levels of saturated fat and may have a positive benefit on gut health with greater formation of short-chain fatty acids by gut bacteria. However, a major disadvantage currently is the high salt content, and some products contain coconut oil and hence are high in saturated fat.

These results are reassuring given the need to move away from meat consumption for environmental concerns. Demonstrating that PBMAs can be healthier than meat should hopefully support their inclusion within public health guidelines. You can listen to the lead author of this study, Joshua Gibbs, on the In a Nutshell podcast.

O’Hearn, M. et al. (2023) ‘Incident type 2 diabetes attributable to suboptimal diet in 184 countries’, Nature Medicine, 29, pp. 982–995. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02278-8

Dietary risk factors and type 2 diabetes

Despite understanding a huge amount about the causes of type 2 diabetes, the incidence globally continues to rise. This huge study provides us with a figure for the contribution of dietary factors to the risk of type 2 diabetes. Suboptimal diets were found to be implicated in 14 million or 70% of new cases of type 2 diabetes, with a range of 52–86% depending on geographical region and affecting men more than women. Excess intake of harmful dietary factors was shown to be a greater contribution to this risk than insufficient intake of protective factors. Overall, the specific dietary factors can be summarised by the fact that diets are currently too high in red and processed red meat, sugar-sweetened beverages and insufficient in whole plant foods as seen in this figure. Of note, yogurt is considered protective as controlled studies have shown a positive impact on glucose regulation, likely due to the probiotic effect and impact on the microbiome. Potatoes were assumed to have a negative impact on diabetes risk due to prior studies showing an association with being overweight, obesity and type 2 diabetes. The results suggest a direct effect of these dietary factors that were not merely due to their impact on body mass index.

These results are truly depressing and confirm that in most cases, type 2 diabetes is entirely preventable. The accompanying editorial makes the following statements:

- A sustainable food environment that ensures the availability of health-promoting foods, while limiting foods clearly shown to promote ill health, requires large-scale government action.

- There must be less reliance on refined grains and red meats, with increased production of environmentally sustainable whole grains, vegetables, fruit and legumes – an important source of plant-based protein.

- Population health and environmental sustainability require much stronger action – advice that governments ignore at their peril.

The Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group (DNSG) of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) (2023) ‘Evidence-based European recommendations for the dietary management of diabetes’, Diabetologia, 66, pp. 965–985. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-023-05894-8

Dietary guidelines for diabetes emphasise plant-rich diets

This is a very useful and timely guideline given the discourse amongst health professionals around ‘the best’ dietary approach for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. For prevention of diabetes, the recommendations align with general healthy eating guidelines that all include an emphasis on whole plant foods, e.g. Mediterranean, Nordic and vegetarian diets. The key is to avoid being overweight and obesity, which is much easier when following a dietary pattern that is plant rich.

For diabetes management and remission, there is acknowledgment that a number of dietary approaches that support weight loss can be effective. However, there is a strong emphasis on consuming a fibre-rich diet through the consumption of whole grains, vegetables, legumes, seeds, nuts and whole fruits in order to meet fibre recommendations of 35g/day. Very low carbohydrate intakes, such as with ketogenic diets, are not recommended although it is acknowledged that carbohydrate counting may be a useful approach to determine mealtime insulin dose. The guideline also notes that low-carbohydrate plant-based diets may be useful.

There are clear recommendations that dietary fats should come from plant-based foods and that saturated fat intake, mainly from animal-sourced foods, should be minimised. Regarding protein intake, it is stated that: “Insufficient evidence exists from clinical trials in people with type 2 diabetes to indicate preferential intake of either animal or plant protein. However, high animal protein diets may exceed recommendations for saturated fat intakes (<10% total energy), with serum cholesterol concentrations and markers of blood glucose control generally lower for diets higher in protein from plants.”

Further evidence supporting a healthy plant-based diet for reducing the risk of diabetes comes from this new analysis of data from UK Biobank study participants. As expected, in this population of 113,097 people followed for 12 years, the risk of type 2 diabetes was 24% lower in those who adhered most closely to a healthy plant-based diet. However, this was not only due to the association of a plant-based diet with a lower body mass index (BMI) but was also mediated by lower levels of inflammation and lower IGF-1 levels, along with better heart and kidney health. The researchers conclude: “A shift towards more environmentally friendly plant-based diets can have co-benefits in diabetes prevention beyond lower BMI among people following healthful plant-based diets.”

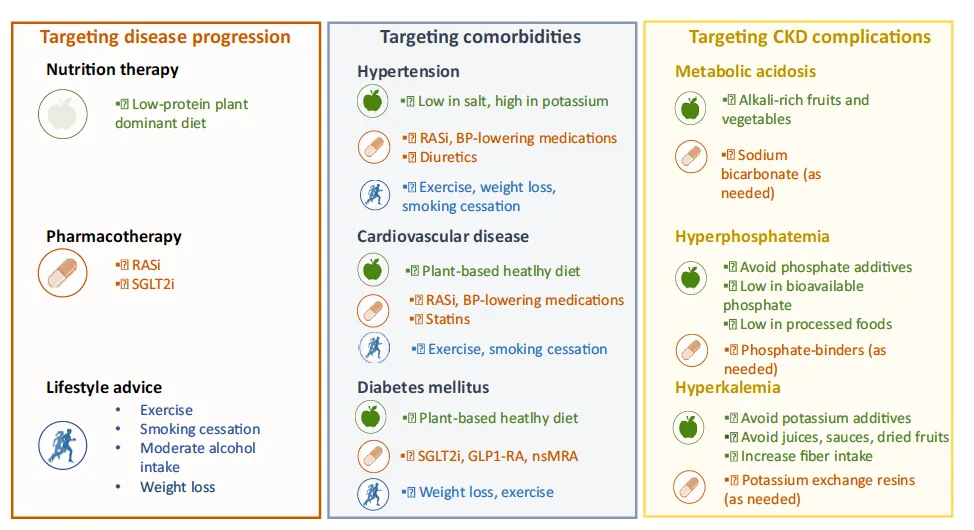

Joshi, S. et al. (2023) ‘Risks and benefits of different dietary patterns in CKD’, American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 81(3), pp. 352–360. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.08.013

Diet patterns and kidney disease

Cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes are key risk factors for kidney disease. This review summarises what we know about diet and kidney health. Evidence for various diet patterns is reviewed, including Mediterranean, low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets, Western diets, plant-based diets and intermittent fasting. Overall, the weight of evidence supports a diet pattern that is high in unprocessed whole plant foods, whilst minimising/avoiding animal foods. This is because plant-based diets are high in fibre and unsaturated fatty acids, lower in protein and low in saturated fat. Although low carbohydrate/ketogenic diets can be associated with weight loss and better glucose regulation in the short term, the concern is that the higher protein and saturated fat intake can increase the work of the kidneys, increase the acid load, elevate blood cholesterol levels and in the longer term increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and early death. There are currently no data on low carbohydrate plant-based diets and chronic kidney disease (CKD). There is currently insufficient evidence for recommending intermittent fasting in the setting of CKD.

The authors conclude: “a recurring theme of these healthy diets is the consumption of unprocessed, whole, plant-based foods, with a growing body of literature showing the potential benefits for patients with CKD.”

The authors conclude: “a recurring theme of these healthy diets is the consumption of unprocessed, whole, plant-based foods, with a growing body of literature showing the potential benefits for patients with CKD.”

Walrabenstein, W. et al. (2023) ‘A multidisciplinary lifestyle program for rheumatoid arthritis: the ‘Plants for Joints’ randomized controlled trial’, Rheumatology, 62(8), pp. 2683–2691. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac693

Lifestyle intervention for rheumatoid arthritis

Randomised studies are the holy grail of medical research. Nutrition interventions are notoriously difficult to carry out, so these studies are in general small and of short duration. However, they play an important part in providing corroborative evidence for the results shown in observational studies.

There is plenty of evidence that healthy diet patterns, high in plant-based foods, reduce the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and may be beneficial for management of the condition. Over the decades there have been non-randomised dietary interventions of vegetarian and vegan diets with or without a period of fasting or other food eliminations. More recently, researchers at PCRM conducted a randomised, crossover study over 16 weeks of a low fat, healthy vegan diet, including elimination and reintroduction of certain trigger foods, and demonstrated benefit in symptoms.

The ‘Plants for Joints’ study is a well-designed, assessor-blinded, randomised 16-week lifestyle intervention of a whole food plant-based diet, physical activity and stress management in people with mild to moderate rheumatoid arthritis. Disease activity was measured using the DAS18 score (disease activity score based on 18 joints). The control group received usual care. Medication was kept stable three months before and during the trial whenever possible.

The results showed that compared to the control group (n=37), the intervention group (n=40) had significant improvement in disease activity and metabolic health with reductions in body weight and body fat, HbA1C and LDL-cholesterol. Depression, fatigue, pain interference and physical function did not change. Although there were reductions in markers of inflammation (ESR and CRP) in the intervention group, these changes were not statistically significant. As expected, those participants who made the most changes had the greater benefit. There was demonstrable improvement in diet quality in the intervention group, however it is not possible to know which part of the intervention was responsible for the improvements seen.

To take account of the short duration of this study, the control group will be offered the intervention after the trial, and researchers will follow all participants in a two-year observational extension study including cost-effectiveness, body composition, bone mineral density, critical nutrients and a medication-tapering protocol for patients in remission. We look forward to the results.

The study team have also published their similar intervention for people with osteoarthritis. Sixty-four participants, mostly female, with osteoarthritis were included in this randomised study. The mean age was 64 years and the mean BMI 33 kg/m2. The results showed that participants in the intervention group had significant benefits to their metabolic health as they lost weight, reduced their fat mass and waist circumference and lowered LDL-cholesterol and glucose levels. The intervention group also had significant improvements in arthritis symptoms, including reduction in pain and stiffness and improvement in physical functioning (31–38% improvement). The analysis suggested that these effects were not purely due to weight loss. There was also a reduction in inflammation as demonstrated by a fall in CRP levels. Participants in the intervention group were also able to reduce their use of medications.

The lifestyle programme was found to be acceptable to patients with a low dropout rate and a good level of adherence. However, the individual contribution of each lifestyle change is difficult to determine. We do know from a prior randomised study that a whole food plant-based diet alone can have significant benefits.

Overall, these results are hugely promising as they provide an evidence-based treatment option for patients that is free from side effects and has the potential to improve symptoms of osteoarthritis alongside important benefits to metabolic health. I look forward to hearing about the longer-term follow-up of these participants.

Zhao, Y. et al. (2023) ‘Low-carbohydrate diets, low-fat diets, and mortality in middle-aged and older people: a prospective cohort study’, Journal of Internal Medicine, 294(2), pp. 203–215. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13639

How to do a low-carb diet well

The popularity of low-carbohydrate diets continues amongst healthcare professionals. Despite some short-term benefits there remain concerns about long-term health outcomes and sustainability. This large study investigated the impact of low-carb and low-fat diets on mortality. The analysis included 371,159 participants aged 50–71 years from the NIH-AARP (National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study) prospective cohort study who had been followed for a median of 23.5 years. Dietary data were analysed using difference scores: overall, healthy, and unhealthy low-carb and low-fat diet scores. Of note, the low-carb diet was not very low in carbohydrates with the lowest category being <40% of energy from carbohydrate. The lowest category for fat consumption was <20% of energy.

The researchers found that low-carb diets were associated with a 14% higher risk of death, with unhealthy low-carb diets high in animal fat and protein associated with a 17% increased risk of death. Overall and unhealthy low-carb diets were associated with a 12% and 15% increased risk of cardiovascular death respectively and a 14% and 17% increased risk of death from heart disease. Overall and unhealthy low-carb diets were also associated with an 18% increased risk of death from cancer. However, if the low-carb diet was low in refined carbohydrates, higher in unsaturated fats and plant protein then there was a small 5% reduction in the risk of overall death.

An overall low-fat diet was associated with a 9% reduction in risk of mortality. Interestingly, even an unhealthy low-fat diet had a small 2% reduction in mortality. If the diet was a healthier version of a low-fat diet, high in healthy carbohydrate-rich foods (whole grains, whole fruits, legumes and non-starchy vegetables), plant protein and low in saturated fat, there was an 18% reduction in the risk of death, 16% reduction in cardiovascular death and 18% reduction in cancer-related death. In contrast, less healthy low-fat diets which were high in refined carbohydrate and animal sources of protein had a very limited impact of mortality reduction.

Researchers also conducted a substitution analysis, which showed that replacing 3% of calories from saturated fat with any other macronutrient resulted in a lower risk of death. Similarly, replacing refined carbohydrates with plant protein or unsaturated fats resulted in a lower risk of death. The greatest benefit was seen when saturated fat was substituted for plant sources of protein.

The authors conclude: “Our results suggest that a healthy low-fat diet with minimal saturated fat intake would be an effective dietary strategy for healthy ageing among middle-aged and older people.” This is easily achieved with a plant-exclusive diet. Interestingly the authors point out that despite the perceived inferiority of plant protein composition compared with animal protein (an outdated notion), the participants in this study had superior outcomes when prioritising plant protein even though they were at higher risk of sarcopenia based on their age.

Overall, the study confirms that it doesn’t really matter about the macronutrient combination. Low-carb and low-fat diets can both be healthy if they are composed of health promoting foods, i.e. plant sources of fat and protein and high-quality carbohydrate rich foods (fruits, vegetables, whole grains and beans).

I am reminded of another recent paper that performed a meta-analysis of three studies of low-carb, ketogenic diet in people of normal weight to establish the effects on blood lipid levels. The results clearly showed that a ketogenic diet led to detrimental increases in total and LDL-cholesterol. Additional research has also highlighted the increased risk of colorectal cancer in individuals consuming an animal-based low-carb diet.

Ghorbani, Z. et al. (2023) ‘Overall, plant-based, or animal-based low carbohydrate diets and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies’, Ageing Research Reviews, 90, 101997. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.101997

Low-carb diets can be healthy when they are plant-based

More data suggests that lowering carbohydrate consumption in the diet may be beneficial but only when carbs are replaced by plant sources of fat and protein. This new systematic review and meta-analysis examined the impact of plant-based, animal-based and general low-carb diets on mortality. It included 10 prospective cohort studies with more than 400,000 participants. Dietary data were scored according to carbohydrate content, plant and animal sources of fat, and protein. Overall high adherence to a low-carb diet and animal-based low-carb diet did not have an impact on overall/all-cause mortality (neither positive nor negative). However, a low-carb plant-based diet reduced all-cause mortality by 13% with each five-point increase in plant-based low-carb score reducing mortality by 4%. In contrast, overall and animal-based low-carb diets were associated with a 14% and 16% increased risk of dying from cancer respectively. A plant-based low-carb diet did not impact risk of cancer death. There were no positive or negative associations between a low-carb diet and risk of cardiovascular death.

So, if you want to try a lower carbohydrate diet to see if you may gain benefits for weight management or glucose regulation, then the science shows you should replace carbohydrates in the diet with plant sources of protein and fat. In general, these and prior data suggest keeping carbohydrate consumption between 40–70% of energy intake is optimal and not going too high or too low. You can read more about low-carb diets and the impact on health here. If you want to try a low-carb plant-based diet, this article will provide some pointers.

Cordova, R. et al. (2023) ‘Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: a multinational cohort study’, The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 35, 100771. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100771

Not all ultra-processed foods are foods created equal

There has been a lot of attention on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) recently, and rightly so. However, some of this attention is being used to create a negative narrative around vegan diets, suggesting that products frequently consumed by vegans fall into this UPF category. For example, plant milks and plant-based meat alternatives are often deemed to be highly processed and hence considered by some to be unhealthy. This is then being used as an excuse to continue promoting the consumption of meat, milk and eggs as they are ‘natural’ and ‘unprocessed’.

This new analysis clearly shows that not all UPFs are created equal and thus highlights issues around the NOVA classification. This prospective cohort study included 266,666 participants (60% women) from the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) study. The median age at recruitment was 52 years and participants were followed for a median of 11.2 years. The mean consumption of UPFs (without alcoholic drinks) for men and women was 413 g/day and 326 g/day respectively. This corresponded to a proportion of 34% kcal and 32% kcal of UPFs in the daily diet among men and women (much lower than the UK consumption where more than half of calories are from UPFs).

As expected, UPF consumption was associated with an increased risk of cardiometabolic conditions – cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes – and cancer. Each 260g/d increment in intake was associated with a 9% higher risk of these conditions (that is, of developing two of these diseases). Associations with higher BMI did explain some but not all of this increased risk. However, the increased risk was specifically associated with the consumption of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages, animal-based products (including processed meats) and sauces, spreads and condiments. There was no increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer with consumption of other types of UFPs, such as breads and cereals, sweets and desserts, savoury snacks, plant-based alternatives (meats and milks), ready to eat/heat and mixed dishes. In fact, the consumption of bread and cereals was inversely associated with these chronic conditions.

The results suggest that there may be non-nutritional reasons for the health harms associated with certain UPFs, including alteration of the food matrix, inclusion of certain food additives during processing (e.g. aspartame) and contaminants from packaging material (e.g. bisphenol A). These may affect endocrine pathways or the gut microbiome and contribute to subsequent disease risk. However, each product should be assessed on its own merit.

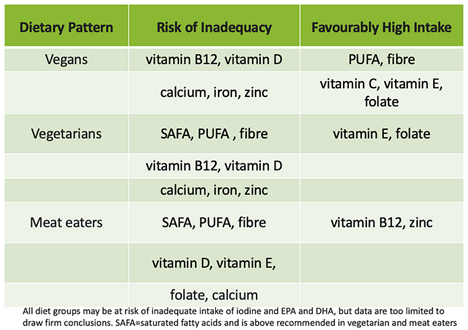

Neufingerl, N. and Eilander, A. (2023) ‘Nutrient intake and status in children and adolescents consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review’, Nutrients, 15(20), 4341. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204341

Plant-based diets for children and adolescents

This is a very useful study, especially since vegan or plant-based diets for children remain controversial amongst some groups of health professionals. This study, similar to one published by the same authors on adults, aimed to evaluate the nutrient intake and status of children and adolescents (2–18 years) consuming plant-based (i.e. vegetarian and vegan) diets compared to those of meat-eating children. A systematic literature review of studies published between 2000 and 2022 was conducted. Mean intake and status data of nutrients were calculated across studies and benchmarked to dietary reference values and cut-off values for nutrient deficiencies. A total of 30 studies were included (15 in children 2–5 years, 24 in children 6–12 years, and 11 in adolescents 13–18 years).

The results showed that in all diets there were risks of inadequate intakes of vitamin D and calcium. Regarding energy and protein intakes, most studies showed all diet patterns met recommended requirements. As expected, fibre intake was highest amongst vegans and insufficient in meat eaters. Saturated fatty acid intake was higher and PUFA (polyunsaturated fatty acid) lower than recommended in meat eaters. Insufficient and mixed data were present on intake of omega-3 fatty acids – EPA and DHA – and limited data were available for iodine intake. Iron intakes were deemed to be lower in those consuming meat-free diets due to the known lower bioavailability of iron from plant sources. Iron stores (ferritin levels) were lower in vegans and vegetarians, but this did not result in an increased risk of anaemia with no significant differences found in haemoglobin levels between diet groups. Similarly with zinc intake, bioavailability from plant sources is lower, but studies did not demonstrate deficiency in children consuming meat-free diets. Vitamin B12 needs to be supplemented in vegan diets.

Overall, the authors concluded that all three diet patterns could benefit from being optimised and that vegetarians and meat eaters could benefit from consuming more plant foods. Whereas for children on meat-free diets it is essential they consume a large variety of nutrient-dense plant foods (i.e. high in iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and vitamins B12 and D) and/or foods that are appropriately fortified with these micronutrients, e.g. dairy and meat alternatives. “Children on a plant-based diet as well as meat-eating children are at risk of inadequate nutrient intakes … Increasing consumption of a variety of nutrient-rich plant foods, in combination with food fortification and possibly supplementation, can help children and adolescents have more sustainable diets that are healthier and meet all nutrient requirements.”

Check out this excellent factsheet on plant-based diets for children.

Hu, J. et al. (2023) ‘Association of plant-based dietary patterns with the risk of osteoporosis in community-dwelling adults over 60 years: a cross-sectional study’, Osteoporosis International, 34(5), pp. 915–923. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06700-2

Plant-based diets and bone health

There has been concern raised around the impact of meat-free and vegan diets on bone health with three prior studies showing an increased risk of fracture in vegetarians and vegans. The data are of course nuanced and I have previously summarised my thoughts on the topic in this article. Nonetheless, vegans and those following a 100% plant-based diet should pay attention to bone health, which involves more than just diet and should incorporate all pillars of lifestyle medicine.

It is nonetheless reassuring to see two publications using the plant-based diet index (PDI), which provides a way of assessing the impact of a plant-based diet on health outcomes, whilst addressing the issue of diet quality.

The first study is a cross-sectional study from China and included 9,613 community-dwelling adults over the age of 60 years. Sixty-two point eight percent of participants were female and 19.2% (1,848) had a diagnosis of osteoporosis. A healthy plant-based diet was found to reduce the risk of osteoporosis by 36%, even after adjustment for other lifestyle-related factors. In contrast, an unhealthy plant-based diet increased the risk by 41%. The association of the healthy PDI with the risk of osteoporosis was found to be more pronounced in people over 80 years of age and in female participants. In terms of single foods, whole grains, fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, nuts, legumes and tea were found to be major contributors to the benefit seen for osteoporosis. In contrast, among unhealthy plant foods, higher intakes of refined grains, sugary drinks and desserts were associated with a higher risk of osteoporosis. Of note, seaweed, egg and fish consumption was also found to be associated with better bone health, whereas meat was found to be harmful. Dairy consumption was overall neutral.

The second study is a case-control study of post-menopausal women with osteoporosis, including 131 cases and 131 controls. The association between the plant-based diet index and bone mineral density in the femoral neck and lumbar vertebrae was assessed. A healthy plant-based diet was shown to be associated with better bone mineral density, whereas the reverse was true for an unhealthy plant-based diet. The authors conclude: “Overall, the findings indicated that in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, a healthy plant-based diet could prevent bone loss, and an unhealthy plant-based diet might have detrimental effects”.

I accept that the two studies are not of the highest quality, but they do provide some reassurance and guidance on how to optimise a plant-based diet. As always, quality of the diet is key.

Monteyne, A.J. et al. (2023) ‘Vegan and omnivorous high protein diets support comparable daily myofibrillar protein synthesis rates and skeletal muscle hypertrophy in young adults’, The Journal of Nutrition, 153(6), pp. 1680–1695. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.02.023

Vegan diets can support athletes

This might sound like an obvious statement to make given the growing number of elite athletes who thrive and excel on a plant-based diet. Nonetheless, there remains scepticism amongst those following an omnivorous diet about whether a plant-based or vegan diet can support equivalent muscle growth.

This small but useful study from the UK asked the question as to whether a vegan diet can support resistance training-induced skeletal muscle remodelling to the same extent as animal-derived protein sources. In phase 1 of the study, 16 young adults with a median age of 23 years were assigned to a 3-day high-protein (1.8g/kg) dietary intervention of protein either derived from animals or plants. At the same time, they performed daily unilateral leg resistance exercise. Phase 2 involved 22 young adults who completed a 10-week, high-volume (5 d/week), progressive resistance exercise programme whilst consuming either an animal-based or plant-based diet. Mycoprotein products were used as substitutes for animal protein sources. Various measures of muscle protein synthesis were taken before, during and after the intervention. Overall, the results showed equivalent results in both groups with all participants managing to increase lean muscle mass. The authors conclude: “a carefully designed vegan diet is capable of supporting optimal skeletal muscle adaptive responses to resistance training.”

Another recent study called the SWAP-MEAT Athlete study enrolled 12 recreational runners and 12 resistance trainers who were assigned to three diets – WFPB (whole food plant-based), PBMA (plant-based meat alternative), and Animal – for four weeks each, in random order. During the WFPB phase, participants consumed at least two meals consisting of vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts and seeds, and whole grains each day. Common meals consisted of protein sources including quinoa, beans and tofu. During PBMA, participants consumed at least two servings of plant-based meat alternative protein sources per day. Common protein sources included Beyond Burger, Impossible Burger and Gardein. No consumption of animal meat was allowed. Fish consumption was allowed once per week, which seems a shame and unnecessary. The Animal group had to eat two meals with red meat or poultry per day, keeping fish consumption to once per week.

The aim of the study was to assess the impact of two different predominantly plant-based diets on endurance and muscular strength. The results showed no significant difference in any of the measures of performance assessed between the diet groups. Amazingly the authors state: “Our study is one of the first to investigate plant-based meat alternatives and athletic performance, and to our knowledge, this is one of the largest randomized crossover trials (n = 22) conducted on plant-based diets and athletic performance.” So, another green light for athletes to consume plant-based diets, especially when there will be expected benefits for cardiometabolic health.

Damasceno, Y.O. et al. (2024) ‘Plant-based diets benefit aerobic performance and do not compromise strength/power performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, British Journal of Nutrition, 131(5), pp. 829–840. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114523002258

Plant-based diets and atheletic performance

This new systematic review meta-analysis included four studies evaluating the effects of plant-based diets on aerobic performance and six studies evaluating impacts on strength/power performance. Four studies used a vegan diet and six used a lacto/ovo-vegetarian diet. Two studies had women and eight had men as participants.

The results showed that a plant-based diet had a positive effect on aerobic performance and no impact (negative or positive) on strength/power performance. As expected, those following a plant-based diet had a lower body mass index. The authors conclude: “despite the controversy surrounding the adoption of non-carnivorous diets by athletes, when considering the practical effects of plant-based diets on physical activity, it seems that these diets do not compromise exercise performance.”

If you want some more in-depth detail on how to adopt a healthy plant-based diet to support athletic training, why not download this fantastic resource called the Plant-Based Playbook from Switch4Good. If you are new to sports or just keen to get involved with a fantastic new campaign, join me and many others in signing up for Running on Plants.

Stoodley, I.L., Williams, L.M. and Wood, L.G. (2023) ‘Effects of plant-based protein interventions, with and without an exercise component, on body composition, strength and physical function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’, Nutrients, 15(18), 4060. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15184060

Plant protein can support older adults

An ongoing concern around plant-based diets is the ability to support healthy ageing and prevent frailty and sarcopenia (progressive and generalised loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength and performance due to ageing). This comes from rather outdated viewpoints that animal-sourced protein is superior to plant sources.

This systematic review and meta-analysis bring together data from 13 randomised studies to summarise and evaluate the effects of plant-based protein interventions compared to a placebo on body composition, strength and physical function in older adults (≥60 years old). The secondary aim was whether exercise improved the effectiveness of plant-based protein on these outcomes. The studies were conducted in United States (n = 3), Japan (n = 3), Iran (n = 2), Netherlands (n = 1), China (n = 1) and Brazil (n = 1). In total, there were 806 participants included from studies published between 2002–2022. The study intervention duration varied between 12 weeks to 1 year. The overall daily dose of protein varied from 0.6g to 60g and all studies used soya as the plant protein. Most studies provided protein supplementation daily. The control group mostly received animal-sourced protein. The study reported outcomes for body composition, strength and physical function.

The results showed that plant proteins (soya) were comparable to the control interventions including animal protein, exercise only, exercise plus animal protein, or no intervention controls. However, plant protein interventions were better for reducing fat mass. For strength and physical activity outcomes, plant protein interventions were comparable to the animal protein control groups. Interestingly, when compared to studies with exercise components, plant-based proteins performed better without an exercise component.

Overall, the results are reassuring that plant proteins can be effective at supporting healthy ageing. It would be useful to have more studies using protein sources other than soya and assessing the impact of an overall healthy plant-based dietary pattern on outcomes in older adults. We do have a recent study from Taiwan which included 12,784 participants aged 50 years and older followed for eight years, which showed that a healthy plant-based diet was associated with a substantially lower pace of ageing.

This new review paper on diet strategies for promoting healthy ageing is well worth reading.

Ólafsson, B. (2023) Eating meat is bad for climate change, and here are all the studies that prove it. Available at: https://sentientmedia.org/meat-climate-change-studies/

Environmental impacts of diet choices

We have decades worth of data demonstrating that vegan and plant-based diets have the lowest environmental impacts, yet the meat and dairy industry keep putting forward misinformation to support the continued consumption of their products. This paper from 2023 is an excellent addition to the subject and is described as the most comprehensive analysis of food consumption and its impact of production on the environment. It uses dietary data from the 55,504 participants of the EPIC-Oxford study, a UK-based study cohort in which around a third of participants are vegetarian or vegan and have long follow-up. The study divided participants into vegan, vegetarian, pescatarian, low (<50g/day), medium (>50g per day) or high (>100g/day) meat eaters and analysed the impact of these dietary patterns on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, eutrophication risk and potential biodiversity loss using food level data from a review of 570 life-cycle assessments covering more than 38,000 farms in 119 countries. Crucially, the dataset took into account how and where a food is produced.

There is much detail in this open access paper, but the conclusions are simple and obvious. Any reduction in animal foods in the diet has a significant beneficial impact on all aspects of environmental health that were examined. Lower meat diets have half the CO2 impact of high meat diets, and vegan diets half the impact of lower meat diets. Vegan diets, regardless of the foods consumed, have significant advantages compared to non-vegan diets with around a 50% lower impact for all indicators examined. The biggest difference seen in the study was for emissions of methane, which were 93% lower for vegan diets, compared to meat-based diets. Not that I like saying this, but if you can’t or won’t go vegan then please substantially reduce your consumption of animals and their associated products. Every little step away from eating animal-sourced foods is a win for the planet and the environment with likely benefits for your own health and, of course, the animals.

I have to copy the whole concluding paragraph: “There is a strong relationship between the amount of animal-based foods in a diet and its environmental impact, including GHG emissions, land use, water use, eutrophication and biodiversity. Dietary shifts away from animal-based foods can make a substantial contribution to reduction of the UK environmental footprint. Uncertainty due to region of origin and methods of food production do not obscure these differences between diet groups and should not be a barrier to policy action aimed at reducing animal-based food consumption.”

This excellent article in Sentient Media summarises key studies that demonstrate the benefits of a plant-based diet for planetary health. It highlighted this study from 2023 demonstrating that by replacing half of the meat we eat with plant-based alternatives, by 2050 we could reduce GHG emissions from the food system by 31% and if we reduced meat consumption by 90% we could reverse biodiversity loss. Another excellent report points out that even small dietary changes have a big environmental impact. Replacing 30% of meat with plant proteins could offset almost all global aviation emissions, free up an India-sized carbon sink and save 7.5 million swimming pools worth of water a year.

The greatest impact comes from removing red meat and dairy from the diet, the production of which – according to the 2023 Lancet countdown report – contributes to 57% of agricultural emissions whilst being responsible for 16% of all diet-related deaths (1.9 million). In the UK, the agricultural sector contributed almost 45% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, with red meat and dairy accounting for 74% of all emissions related to the local production of agricultural products and 70% of all emissions related to the consumption of agricultural products (either locally produced or imported). In addition, in 2020 42,000 deaths in the UK were associated with excessive consumption of dairy, red meat and processed meat, and 70,000 deaths were associated with insufficient intake of nutritious plant-based foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds.

Luckily, we don’t need to compromise our health to save the planet. A plant-based diet is optimal for human and planetary health and kindest to all the animals we share this earth with.

The views expressed by our Research News contributors are not necessarily the views of The Vegan Society.